Mahone and Von Moltke

the Younger and the worlds they were never allowed to make.

All this and more in the new addition--and entries to follow.

The Great Stories

Begin With "What if..."

I don't like the world. So I'm remaking it.

This is all thinking aloud. Bear with me.

There are other versions of the times in which we live where perhaps the world is not altogether better, just different. Still, I would like to breathe that air, stroll those avenues, read the newspapers at the sidewalk café and amid the clatter of cups and silverware, eavesdrop on the day's talk, and gain a sense of what these people are anxious about. Surely the daily thrum of doomstering would on occasion give rise to a pause among a few of them to wonder: what if we lived in a different way, what if some things we accepted as immutable fact were only passing shades in another time and place...

Worldlines

I am able to conjure these realities only by research and imagining situations, and to set characters aloose in them. Philip K. Dick mastered this in his The Man In The High Castle and Len Deighton in SS/GB. Both were novels of World War II what-ifs. The reader knows this isn't the "real world" while the characters have no knowledge of any other. Except in Dick's book, where the characters begin to understand that their reality of a Japanese-German victory is not the only one.

I like one of the current far-edge speculations of physics, that of "brane" theory that posits that time and space combined are like a loaf of bread and from it can be cut many slices, many realities. That's exciting to me and reintroduces a sense of "Wow" to things.

Here are two such "worldlines" that I've spent some time thinking and reflecting about. They are not the major part of my creative endeavor just now, but provide some imaginative stimulation and potential for future exploration.

What if the Virginia Readjuster Party of 1877-1883 had existed longer and managed to shape state law into the 20th century?

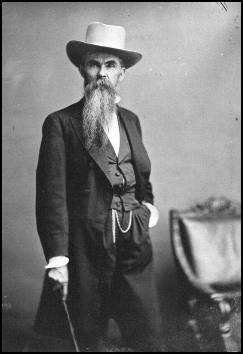

The Readjusters were led by former Confederate Major General William Mahone. Mahone was a tiny, compact man, known for his high-pitched voice, fastidious dress, railroad millions, and his uncontested bravery during the conflict. He arose in the post-Reconstruction era to lead his own brand of maverick party built on the platform that "capitalized on dissatisfaction engendered by the ruling Conservatives’ [Democrats and Republicans] decision to honor their pre-war and post-war debt at the expense of public services like the fledgling public schools," as historian Renan Levine describes it.

Mahone and his allies built a wobbly coalition between working class whites and enfranchised blacks. What if they managed to not only survive but transform into what I'll term the New Dominion Party?

Extreme Makeover

How do I accomplish this? By releasing a bio-electro-chemical agency that blankets the Commonwealth and reprograms the synapitc firings in the brains of most of the population. This especially is the case with lawyers, judges, ministers and professors and small town barber shop politicians, both black and white.

Imagine, though, how strange it would be when former Confederate veterans turned politicians visit the home to seek support of young Maggie Lena Walker (1867-1934)-- who'd by 1883 protested the inequality of white and black high school graduation ceremonies by organizing a black student school strike, the first such response in the U.S. to unequal treatment. A young black man in a hurry, John Mitchell Jr. (1863-1929), who'd rise to become a firebrand editor and a businessman in Jackson Ward, would be asked by these white leaders in 1888 to support the upcoming revisions of the Virginia Constitution.

Attorney Giles B. Jackson and minister/ businessman William Wasington Browne would also participate in various discussions to hear, perhaps with incredulous expressions, the plans for Virginia's future in which they were to play prominent parts. The drafted clauses for the new state constitution abolished poll taxes and all other voting restrictions based on race.

Likewise, Lynchburg women's suffrage and social activist Orra Henderson Moore Gray Langhorne (1841-1904) would've been asked the favor of a visit, and the Virginia suffrage movement would've taken on a different course than in the present worldline. Although Virginia women gained the right to vote in 1920 with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the Virginia General Assembly did not ratify the amendment until 1952. In the new worldline, rather than resistance to the very idea of women and politics, some prominent Virginia leaders awaken to the political power of the vote in the hands of women -- all women.

On the road to Damascus, Virginia

None of these massive social shifts would've occurred with anything approaching ease. Individuals would suffer guilt and depression and other more severe imbalances, and the mental distruption would flash out in violence. Imagine almost an entire state going through a road-to-Damascus sensation: We have been wrong. We must be right and as righteous in this belief as we were zealous in the former world.

That's some tough weight to carry and survive in your personal identity network of family, friends and colleagues, all of whom presumably have been conducting their lives while operating under similar notions to your own.

In Virginia of the 1880s progressive ideas weren't prevalent. By this is meant, for example, the proposition wasn't accepted that everyone in the adult population should participate in democracy no matter race, gender or creed. Not understood was that the concept of far-sighted planning needed to begin in the late 19th century to create for the 20th century. In this way, Virginia of the New Dominion worldline evolved into a sophisticated, advanced, resilient and diverse society and culture. The Great Awakening, or the Miracle of '82, causes an incredible social upheaval througout the Commonwealth.

The consternation incites street violence, lynchings, massed protests and militia marching down Broad Street as protestors armed hasty barricades and occupied Jefferson's Capitol to assure the passage of the new state constitution. New Dominion (Readjuster) Governor John Sergeant Wise (1846-1913) squeaks out a victory over favored Democrat Fitzhugh Lee (1835-1905) nephew of General Robert E. Lee, and a Confederate veteran and accomplished public servant. John Wise was the son of Henry Wise (1806-1876), Virginia's flamboyant anti-secessionist antebellum governor who nonetheless sent John Brown to the gallows. John Wise was a boy soldier at the Battle of New Market.

The Wise Guy

Wise's complete conversion both invigorates the New Dominion cause, and astounds and angers its detractors, which includes members of Wise's own family. During his term as governor (1886-1890) Democrats and Republicans force a constitutional crisis as violence and deaths increase. Southwestern Virginia counties draw up plans and committees for secession from Virginia and to join another state (but West Virginia and North Carolina don't want them).

Wise urges the Virginia Congressional delegation to ask President Grover Cleveland to send troops, but Cleveland's response is that Virginia and the New Dominionists caused these events, thus, the New Dominionists must resolve them. Besides, sending federal troops into a Southern state to quell a dispute that at its center is a question about Negroes--that war was already fought, and Cleveland doesn't want another one.

She's no Lady, she's the Governor

Virginia triumphs, though not without hardship and the rise of such reactionary organizations as the Ku Klux Klan. But, as most of the judiciary and enforcement officials are New Dominionsts, sympathetic, or seeking to retain their jobs, the activities of the Klan and other groups, are mitigated. Lingering racial resentment continues into the 21st century--much as the effects of the Civil War and civil rights still resound in today's Richmond worldline.

These audacious policies are not undertaken without violent conflict, however, a civil rights movement is sparked some 80 years ahead of schedule. A major state constitutional showdown occurs and the new abolishes all restrictions to voting, bringing in white, black, Native American and women -- and that's just for starters.

Virginia ultimately elects Nancy Langhorne to the Virginia state legislature and two terms as Governor (1918–1926 ). Her administrations are lively, productive and historical.

Afterward, she's repeatedly elected to Congress -- instead of her marrying some Brit and becoming Lady Astor in Parliament. She gets her Frederick Williams Sievers statue on Richmond's splendid urbane boulevard, Monument Avenue, and not yet another booted and bearded Confederate/Celtic chieftain on a rearing horse.

Even without the elaborate speculative fiction deux ex machina tinkering, Mahone and his Readjusters in the current worldline controlled the Virginia state legislature, elected congressmen, a Governor, and two U.S. Senators. Then the Readjusters imploded, first due to Mahone's bellicose personality and the patronage-system nature of late 19th century politics, and how negotiating room narrowed for the Readjusters between Democratic and Republican parties, both of which wanted blacks out of the political process and wouldn't consider as outlandish an idea as women getting the vote.

The ruling junta

This regressive and oppressive politics reduced Virginia to a manner of government that resembled the junta of a banana republic, or, more exactly, an antebellum plantation. A few leaders, aided and abetted by overseers and opportunists, ran the state. This situation led to the political system of Harry F. Byrd Sr. and Massive Resistance and a century wasted on the needless distractions of race and socio-economic gerrymandering. Virginia in general and Richmond in specific crossed the threshold of the 20th century politically and socially DOA. Historian Michael B. Chesson summed up the predicament in Richmond After The War 1865-1890:

"Richmond inherited the worst of both the Old and the New South. The racism and conservatism of life before the war became even more embedded in its society, but much of the antebellum graciousness, noblesse oblige, and disdain for money was gone, replaced by…materialism and superficiality…The rights of workers, women, and blacks were little more respected, and the need for a good public school system, for libraries, and for other progressive features of modern urban life were scarcely more recognized in 1890 than in 1860. The tragedy of Richmond after the war was that its white leaders, after two decades of flirtation with progress, returned to a cause that they had all but abandoned and embraced the dead thing with a passion that they had never felt while it lived."

But that's all changed in the New Dominion worldline.

Mahone's triangulation

Mahone receives a much-needed character transplant. He's into triangulating opposing views a century before Clinton. He becomes savvy and immensely diplomatic. He supports the run of exotic independent John Mercer Langston (1829-1897[our worldline, ca.1912 in the New]) in his 1888 bid for Congress. Mahone stumps for Langston despite objections from the supportive but methodical-movement representatives of his own party. Langston wins without the disputes of our worldline. He becomes the first black Congressman from Virginia, and serves a few terms.

Langston in the present worldline bolstered his national reputation in 1888, running for the US House of Representatives. He served for only six months because his victory was contested for 18 months and he was unseated in the next election.

Radical measures

The radical readjusted Virginia Constitution of 1888 created a greater Richmond of Henrico and Chesterfield and a popularly elected regional planning commission whose job it is to look into the future, make extraordinary plans, and figure out practical ways of implementing them. These measures and propositions are then voted on through public referenda. The regional agency owns and operates the transit system, creates a green belt around the city to allow for the maintenance of farmers markets and agricultural co-ops, and gives municipalities powerful zoning and development control tools.

Thus, in the overhauled and streamlined Richmond city administration, the heights of downtown buildings are restricted, and highrises are discouraged, so that Jefferson's Capitol, a temple of democracy, is seen from almost every angle, and there's few inhumane canyons of domineering buildings obscuring the sun.

Many of these municipal reforms are implemented by a great overhaul of the machinery that runs Richmond's government. The New Richmond Movement during 1886-1887 gives the charter an extreme makeover and jettisons almost every vestige of the then-present government.

Until the reforms, the city was administrated by a bicameral city council, an 18-member Board of Aldermen and a 33-member Common Council. This unwieldy system was responsible for hiring and firing. The city was operated by 25 standing committees. To further complicate matters, separate commissions oversaw the police and fire departments and the schools.

The mayor was largely ceremonial and work was done in Council and its committees. Council needed only a simple majority to override a mayoral veto. Even though it was a figurehead position, the mayor's $2,000 salary lured candidates. Historian Christopher Silver points out in his excellent Twentieth Century Richmond,

"Contests for the City Council lacked a two-party base after Democrats purged the racially tainted Republican party in the 1890s. For all practical purposes, the April Democratic primary dictated the outcome of local elections. In 1904, for example, more than five thousand voted in the April primary, while only three thousand turned out on the June 14 election day to cast their votes."

The culmination of the New Richmond worldline's efforts in '86-'87 was an extensive city charter revision that among other things abolished the dreadfully inefficient bicameral City Council, the ward system, and the powerful City Democratic Committee. In their place, New Richmond supporters erected a nine-member city council with a strong mayor elected at large. The government was organized into departments and divided further into offices.

A series of colorful, controversial and eccentric mayors guide Richmond from the 1880s into the 1910s. They include progressive "live wire" and Confederate veteran Carlton McCarthy, fighting editor John Mitchell Jr. -- the first black mayor in the nation, and Lila Meade Valentine, the first woman city executive, and Frank A. Cosby, avowed socialist, who served as the financial secretary of the Plumbers' and Steamfitters' local and whose candidacy enjoyed the demonstrative support of Richmond labor, and the enormously popular and active "streetcar mayor" George Ainslie.

The New Richmond

The New Worldline Richmond population is upward of 3.5 million people who live in the metropolitan region that includes the old city of Richmond, Henrico and Chesterfield, and Hanover (which joined Greater Richmond in 1948).

Throughout the state regional educational systems were consolidated and integrated by the 1888 Constitution. This caused the most and longest-lasting disruption that, in some communities, still exists. Many white families who could not afford private schooling formed their own, though in some cases legal action was undertaken to block these self-styled "academies." Other families pack up their households and moved from the state which, in their view, had gone stark raving crazy.

In the Richmond region through the 1890s public schools were selectively placed within communities--whether Chester or Church Hill-- accessible either by walking or within easy reach of public transit. Huge public brawls erupted in school organization meetings about where lines should be drawn for what schools. The effort was to keep classes small, teachers well-compensated, and students and parents able to get to and from their schools in short periods of time. As the region grew, boundaries received adjustment and new schools were constructed, and the debates continue in the new Richmond worldline as the best way to serve the student population without relying on vehicular transportation.

Gamble's Hill, obliterated by Ethyl Corporation in the current worldline, still stands with Pratt's Castle and some of the most elegant wrought iron porches in the South. Pratt's Castle is one of the nation's most unique bed and breakfast houses. Portions of the James River and Kanawha Canal were unearthed from railroad tracks and other construction, or, otherwise maintained and not premitted to deteriorate or run dry. In the new Richmond worldline, tourists transit from Rockett's to past Tuckahoe Plantation in Goochland County. The Gallego Colonnades by the Great Turning Basin is one of Richmond's most popular and romantic downtown locations for outdoor events and evening strolls.

The John Russell Pope-designed Broad Street station doesn't close and becomes a center for rail travel and other transit options, as does Main Street Station in Shockoe. Virginia's legislators at the state and federal levels stare down Amtrak and refuse to have these stations removed to a suburban "Amshack" as occurred in many other U.S. cities where transportation is not exalted as it is in Richmond, where it was born.

The interstates and parkways, due to activist politics, don't cut through the city but swing farther out. The Big Ditch known as the Downtown Expressway is a double-decker commuter train and tram line. Richmond's transit system is the envy cities. Due to prescient planning with the inception of the electric streetcars in 1888, Richmond has a true spoke-and-wheel system. Two circumferential rings with connecting legs define transportation and development in the region. Tram and commuter rail spurs meet larger rail connections that make Richmond one of the best cities in the Southeast for public transportation. In the Richmond region, development is transit directed, rather than development directing transit.

The Science Museum of Virginia is consructed in the 1970s near Tree Hill Farms in Henrico County's Varina District. The campus makes use of solar, wind and water power, and its extensive botanical gardens and conservatories are regular features in publications world-wide. A commuter rail hub brings visitors in from all points.

The Capitol Theater evolves, expands and is operated in the New Worldline by the Richmond Moving Image Co-op. The William Byrd Hotel continues as a traveler's rest and oasis for rail passengers.

Fulton in East Richmond is an eclectic, desirable model community allowed to evolve through a mixture of demolition and rehabilitation. Hull Street and Old Manchester and Highland Park never decline. Jackson Ward isn't ruthlessly disrupted by the interstate and there is a memorial and performance hall dedicated to actor Charles Gilpin, who originated the role of Eugene O' Neill's Emperor Jones, and entertainer Bill "Bojangles" Robinson. The community is celebrated for its Art Deco-styled cooperative apartment highrises that were designed, built, owned and remain managed by black residents from the 1920s that are, in the New Worldline, highly precious residences that are in the tumultuous process of choosing to go condo.

Those late 19th centrury and mid-20th century houses throughout Richmond in the New Worldline are approaching prohibitive costs for newcomers. But affordable and mixed-income housing ideas--decades ahead of their time in the present worldline--include requirements for developers to include a percentage of affordable housing within the plan of new communities. In exchange, developers receive tax abatements and other incentives. During the early 1910s, historic preservation and community improvement groups form and these groups partner to preserve the city fabric unique to Richmond in collaboration with young, smart city planners, a number of whom are drawn to Richmond from farflung places. The city is earning a reputation abroad as a center for the American future.

Ginter Interrupted

One of the economic engines of this miracle is a major revision in the life and professional ambitions of Major Lewis Ginter (1824-1897 [in New Wordline, 1907]) the New York City Dutchman and life-long bachelor who fought for the Confederacy and made and lost two fortunes, but the third one took. While living in Richmond he traveled the world dozens of times, collected art and antiquities, and lived the life of a a late 19th century tycoon.

Ginter, head of the Richmond-based Allen & Ginter tobacco firm, in 1880 held a contest to build a cigarette-rolling machine. An 18-year-old Lynchburg mechanic James Albert Bonsack devised one that worked, though like any new technology, it experienced cranky fits and starts. Ginter ultimately rejected the machine because of its temperamental nature and he didn't think he could market enough cigarettes to make the investment worthwhile.

Not so the Durham, N.C. businessman James Buchanan Duke.

Bonsack set up a workshop in Duke's factory and on April 30, 1884, the Bonsack machine produced 120,000 cigarettes in a 10 hour day. This total matched the output of 40 experienced hand rollers.

In 1885, Duke contracted to use the machines on a royalty basis and, in a codicil, Bonsack agreed to secret rebates if he leased machines to other manufacturers. By 1889, W. Duke and Company was the largest cigarette producer in the United States. Buck Duke convinced his major competitors, Allen and Ginter of Richmond, William Kimball and Company of Rochester, Kinney Tobacco Company of New York City and Goodwin and Company of New York City to consolidate into the American Tobacco Company.

Ginter tried to fight Duke for the corporate presidency and lost, then the Virginia General Assembly refused to grant American Tobacco a charter as a Virginia Company. For Richmond, it was "the golden moment lost."

As one historian details: "Duke became president and his trust bought out more than 250 other tobacco companies and paid others not to compete. By 1900 it produced more than 90 percent of American cigarettes, 80 percent of snuff, 62 percent of plug and 60 percent of pipe tobacco. It integrated vertically with licorice paste used in chewing tobacco, tin foil, cotton bags, wooden boxes and of course the production and processing of tobacco."

The Duke-ification of Major Ginter

In the New Worldline, Ginter becomes the historic actor, and he, too, is affected by the social paroxysm that overtakes the consciousness of Virginia. Ginter accepts the Knights of Labor, racially integrates his work places despite loud and sometimes bloody objections. He is burned in effigy on Broad Street. If Ginter ever felt threatened by any of these protests, nobody recorded his sentiments, and by his order, all his personal papers were destroyed after his death.

Ginter well sees the vast potential of the machine he called into existence. He is able to absorb other firms into Allen & Ginter, which incorporates in Richmond, and the billions in dollars of profits go straight into Central Virginia, and not New York City.

Ginter, often through a second party and anonymously, gives millions of dollars to institutions of culture and develops such landmark buildings as the Jefferson Hotel and the streetcar suburb of Ginter Park.

Whimsies of a merchant prince

Ginter's last decade isn't marked by mellow slowing of age. He is possessed by a great fury of doing especially in his adopted home town.

One of his strangest fascinations, and indulged as a whimsy of his dotage, is the Commission of Future Academics, consisting of architects and planners for a new Ginter College. The businessman purchases property on and off Broad Street between Belvidere and Lombardy streets, at higher than market value and enters into elaborate agreements with residents and businesses--or their descendents-- to resettle them into his real estate developments. Ginter asked the planners to envision a world-class university of several colleges with an ultimate student population of more than 20,000 students. At the outset, though, Ginter directed that the university use extant buildings where possible and continue to do so, until new construction became necessary.

While he is greatly responsible for the relocation and design of Union Theological Seminary which explores spiritual issues, Ginter focuses on other of his interests, arts, culture, social questions and and civil engineering. He also stipluated that the university operate with no admission restrictions for race or gender and established scholarships for working class students of academic distinction.

During one of his globe-girdling trips he visits Glasgow, Scotland, where he is impressed by the work of Scottish architect Charles Rennie MacIntosh who at the time isn't well-regarded in his own home town. Ginter employs MacIntosh to design arts, administrative and mechanical buildings for a university with locations on and off Broad Street. These plans were then stored and by time Ginter University required them during buildng campaigns beginning from the late 1950s, MacIntosh's blueprints received adaptation to the requirements of contemporary systems.

A singular man

Ginter controlled the largest tobacco industry in the world. However, anti-trust sentiment in the United States caused goverment to follow public clamoring. The prevailing feeling of the public that monopolies were harmful concentrations of power resulted in the dissolution of the Ginter Tobacco by a ruling of the United States Supreme Court in 1911. Four companies calve from the firm.

The health risks become more prevalent and important in the New Worldline Richmond just as they do here, and it is likely we'd still have something like Tobacco Row condos and apartments.

When Ginter dies in 1907 the city shuts down and some 55,000 people attend his extravagant Hollywood Cemetery funeral. The influence of this one man on the city's life won't be matched again.

The New Dominion Party by the late 1930s folds into the Democratic. Few branches opened in other states and politicians seeking higher office from Virginia needed some other identifier than that of "Independent." But by that time, the major goals of the party had been achieved and succeeded beyond anything that Billy Mahone could have ever dreamt of.

There is much more to this Richmond New Worldline -- but a casual reader could only be half as interested in it as me if a compelling story was moved into its streets and rooms.

2) What if somehow the Germans had carried Paris in August-September 1914 and won the First World War?

I've devoted considerable time pondering and fantasizing answers to this puzzlement during my walks around Richmond's early 20th century streets. With so much trouble vexing our present stage one yearns for a different set of primary circumstances.

Suburban sprawl gobbles vast acres due to the post-World War II destruction of the cities caused by flight from taxes and crumbling schools and all supported by U.S. federal mortgage incentives and insurance programs. The development of the cul-de-sac archipelago (Carlisle Montgomery's phrase, not mine) is aided and abetted by an interstate system copied from Nazi Germany's autobahn system and devised through intellectual dishonesty in the days of Cold War paranoia to provide an escape from the cities, when, in the event of a thermonuclear war, there would have been nowhere to go.

The current unpleasantness is fueled by cheap oil. Few people in this country care where it comes from and until very recently, most figured it would last forever. Seque to the post-World War I artificial creation of most of what today constitutes the map of the Middle East. It was primarily cobbled together from the wreckage of the Ottoman Empire. Winston Churchill created Iraq on a napkin to be a kind of Middle Eastern Yugoslavia with such diverse political and religious units that it could be held together only by a strongman--like Tito--which was fine with the Western powers, as Franklin Roosevelt said of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza, "He's a sonofabitch, but he's our sonofabitch."

And it could've all been avoided.

A war conducted by a nervous nelly in a spiked helmet

Helmuth Johannes Ludwig von Moltke the Younger, (1848 -1916), Chief of the German Army General Staff was an arty, occultist nervous nelly who altered the much-labored over Schlieffen Plan and stayed far too behind of his lines during the campaign against Belgium and France in August 1914.

Field Marshal Karl von Bulow got a case of the slows and the more aggressive General Alexander von Kluck could've used the Rumpler Taube reconaissance aircraft utilized so well on the Eastern Front that helped the German victory at Tannenberg. If Von Kluck had had eyes in the air, he would've known about the presence of the in-name-only French Sixth Army and pressed his attack. Or he could've avoided that entire scenario. Von Bulow should've gotten a kick in the pants from Moltke to close up the distance between he and Kluck. Kluck could've swung further west, as planned, and either trapped the British Expeditionary Force or sent it fleeing.

The French government retreats to Bordeaux, surrenders and the British who've not been captured, dogpaddle to Dover, in a 1914 Dunkerque.

Schlieffen's shortfalls

Von Kluck failed to obey the injunction, "let the last man on the right swipe the Channel with his sleeve." Melancholic Moltke, holed up in his chateau headquarters, could see on the maps a gap widening between von Kluck and von Bulow and when von Kluck asked for advice, Moltke ordered him to wheel in closer. It was an error borne of too much distance and too little communication. And, when Belgium's fortified city of Liége fell sooner than expected, two corps reserved to absorb the cost of taking it were sent East to Tannenberg -- because they weren't then needed in the West -- such were the rules of the German war plan. The officer who orchestrated the taking of the fort, Erich von Ludendorff, was one of the architects of the Tannenberg victory.

Now, arguably, the Schlieffen plan was a table-top exercise, a thought problem, that conveniently ignored Belgium's neutrality and used the country instead as a front porch entry to get at the French. Breaking Belgium's borders bedeviled bellicose Britons. German sensibilities wisely left Holland out of the equation as the generals in spiked helmets rightly figured they'd have created too many active enemies and would need a quiet neutral in the West.

The Schlieffen protcols didn't solve the Problem of What To Do With Paris. In 1871, the Germans used big guns to cause death and disruption. The siege tactics worked then, but not without a huge effort and great casualties and the creation of much enmity toward the Bosche.

By mid-August 1914, German forces were exhausted, their supply lines stretched thin, and the British Expeditionary Force was in the mix. Still, the Germans could've won, and while Imperial Germany was no enlightened democracy, it was not Nazi Germany.

Some needed context

Michael Lind, in an essay "Lessons of World War I" for the New America Foundation, sets the context, and the bold type is my addition:

"If Imperial Germany was somewhat less liberal than the British Empire or the United States, it was far more enlightened than Tsarist Russia. And in some areas of science and technology and education and welfare, Kaiser Wilhelm II's Germany was the world 's leading nation.

At the time, many German thinkers contended that their country's bid for European primacy and world power was in the interest of humanity at large. Thomas Mann, for example, argued that Germany represented mystical, intuitive, artistic Kultur-the mean between the extremes of decadent, overrefined, materialistic Zivilisation (symbolized by the U.S., Britain, France and/ or the Jews ) and the barbarism of Russia and the "Orient." Max Weber claimed that only a German victory could save the world from "Americanism."

Others offered a geopolitical justification of the War. Germany, it was said, would overthrow the global hegemony of the "Anglo-Saxons" to establish a multipolar global system, in which one pole would be a German-led Europe. As early as 1900, the influential National Liberal Friedrich Naumann had argued in the following vein: "If there is anything certain in the world, it is the future outbreak of a world war, i.e. a war fought by those who seek to deliver themselves from England."

....

"Had Germany triumphed in World War I, the 20th century, which Henry Luce called "the American Century," probably would have been the German century. Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union were monsters with congenital defects; ideology drove the one to military suicide and the other to economic suicide. A successful authoritarian Germany, by contrast, might have combined rational statecraft with a capitalist economic system. The Kaiser's European empire was dangerous precisely because, unlike the Nazi or Soviet empire, in the long term it might have worked."

How to save 72 million people, plus or minus

And, we are spared these grim figures as Wikipedia lists them, emphasis mine:

"The total estimated human loss of life caused by World War II, irrespective of political alignment, was roughly 62 million people. The civilian toll was around 37 million, the military toll about 25 million, the Allies around 51 million people, and the Axis lost 11 million..There was a disproportionate loss of life and property; some nations had a higher casualty rate than others, due to a number of factors including military tactics, crimes against humanity, economic preparedness and the level of technology."

All this, and no Casablanca. Here's not looking at you, kid.

Would would the French do?

What you do get--and various Internet discussion aboards about this subject (yes, they exist) cannot make up their collective minds--is a France that's been twice thrashed by Germany in 50 years' time.

After the 1871 defeat, Paris was under martial law for five years and the streets ravaged by violence that killed some 30,000 people. The Communards sought control. Probably something similar would've reoccurred -- déjá vú all over again.

Even with Hitler removed from the equation, the history of wars and counter-wars in Europe presupposes another round in the ring for France and Germany. At least by the 1930 France arises spoiling for a fight, first with itself, then the Germans. The French political life could be divided between nationalists and possibly communists. A strong political force, using their own stabbed-in-the-back theory, arises and seeks the return Alsace-Lorriane to the bosom of France, and whatever else the Germans took.

As one observer I think realistically suggests, France would've in this model become a version of Spain in our world's 1930s timeline. Would a Lincoln Brigade have come to the aide of French anti-nationalists?

And without Nazis, no Guernica massacre for Picasso to immortalize although there'd certainly be something for him to paint during this New Worldline version of event. Hemingway, bereft of driving for a World War I ambulance corps and therefore escaping his life-and-art defining injury, writes now instead about revolutionaries and counter-insurgents fighting in the streets of Paris.

Rushing in to Russia

Meanwhile, Russia is alone without French or British help. The Germans actually won their first major WWI victories on the Eastern Front. During the opening guns of late August 1914 the Germans whomped the Russians at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes. Without invasion forces needed in France, that highly efficient German rail system could transport troops and equipment Ost. Then what? Do you follow retreating Russian armies into the nation's interior, and if so, how far? Or do you just fight running battles in Poland? And for how long?

The Germans could create a client state of both Poland and the Ukraine and liberate the Balitc countries, and truncate Russia. This would foment rebellion, but it is unlikely that the Kaiser would send Lenin with a box of gold to St. Petersburg to lead a revolt. There would've been little need for his shenanigans. Instead of Lenin's Bolsheviks, you'd get revolution Kerensky-style.

Anastasia gets to live--but maybe in Doorn

The Czar likely as not would've ultimately been deposed and perhaps escape to a Shah of Iran exile (or, even as Kaiser Wilhelm was after World War I, to retirement in Holland).

Germany might've set up an autonomous White Russian protectorate but this would alienate most Ukrianian nationalists, who didn't want any truck with Bolsheviks, the Czar or Kaiser Wilhelm II. This could lead to an extended guerrilla war on the Russian steppes and further opportunity for a revolution to halt the war. Would Kerensky want to keep fighting as he did in the historic worldline? In this alternate timeline, the entire German army can roll into Russia without France to worry over. The Russians have't experienced four years of massive and demoralizing war. They have the advantage of interior lines while Germans stretch their supply routes futher and deeper into the Russian hinterland.

Perhaps a rump Soviet Republic is set up in the environs of Moscow, but without Lenin, who knows whether such a revolt could gain sufficient traction, or if governing would be possible. And with such a crisis in Russia, perhaps another person, an obscure or unknown figure in our worldline, would be catapulted by events into prominence and leadership.

The Ukraine could've become a proxy war between Imperial Germany and Russia, with the misbegotten Kingdom of Poland stuck in the middle of another one of those sputtering mid-European wars such as what preceded World War I. And with France off to the west boiling to bloody the Germans, perhaps some kind of treaty would be possible between the French and Russian nationalists?

Regardless of what would have occurred, by staving off Stalin and his inheritors, that's some 60 to a 100 million lives saved. No Battleship Potemkin and no Dr. Zhivago.

But wait, there's more with Britian and Austro-Hungary...

In the New 1914, Britain loses some face and a few overseas colonies. Despite the intermarriage of the English and German royal houses, the political relationship between the two nations was in decline from the mid-1890s. They are engaged struggle of great national powers. Britain wouldn't want Germany in possession of a massive North Atlantic fleet nor large colonial holdings in Africa. And the Belgium question remains. Split it up into Flanders and Walloon and make a pretectorate? The Germans leave it alone and keep the British off their necks? Not even in their real world plans were the Germans entirely clear about their intentions.

Further, in the historic worldline of February 1915, the Germans attempted to send an arms shipment to Indian Sikhs and Pakistani Muslims ready to revolt against the British. In this alternate worldline, the mission succeeds and ignites a massive civil war intended to remove the British from India. A compelling, rather wild and wooly account of how this might've turned out comes from Luke Schluesener in his speculative essay, "A Jewel In Whose Crown?" that also widens the view from events in Central Asia and Trans-Caucusus, and the British versus the Ottoman Turks.

The doddering and unwieldy Austro-Hungarian Empire was about ready to split open, war or not, and it is likely the energy released by the forces of war would've dissolved the realm into separate nations based on ethnicity. One Glenn Black devised a plausible alternative time-plan that I'll plunder here for the sake of the discussion. He suggests a new Austro-Hungarian Emperor Karl I effectively makes the clumsy collection of peoples a federation. A constitution is created that invests most power in a prime minister "with the Emperor now a British-style figurhead who gives Royal Assent to Bills." Through elections, the empire dismantles itself into these component parts:

Austria (Austria, Carinthia, Styria)

Hungary (Hungary, Transylvania)

South Slavia (Bosnia-Herzegovina, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia)

Czechland (Bohemia, Moravia)

Slovakia (Slovakia)

Polonia (Galicia, Ruthenia, Bukowina)

No Yugoslavia. No Tito, or at least, not as we know him.

Taki's take on the new and improved worldline

As for the Far East, essayist Taki speculates that Japan would've not needed to rape Nanking and slaughter hundreds of thousands of Chinese. With a free hand Imperial Japan could've formed the "Greater Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere." Without a Nazi Germany, though, it is doubtful they would've tried to snag Hawaii. Mao, says Taki, "would have remained a chainsmoking peasant, unknown outside his village" and that there would've been no Korean or Vietnam War.

The shape and configuration of the Middle East would be--well. Changed from what we know. If the Ottoman Empire lurched along for a few more years, those states that came out of post-World War I efforts to "set things right" wouldn't exist as they do today--and there would likely not be the kind of Islamo-Fascisim that's currently all mixed up in the world's affairs.

No 9-11.

The Bomb

Then, one of the big questions I'm toying with is: who gets The Bomb, and when? My money is on the Germans. Few of the major contributors to the realization of what was corrupted into becoming the atomic bomb would've had reason to leave their home states for fear of war and pogroms. All of them would've remained working in their labs and attending their conferences and exchanging information.

These scientists include the Dane, Niels Bohr, Lise Meitner "the German Madame Curie" -- although a Swiss working in Berlin, Hungarian Leo Szilard and Italian Enrico Fermi, Germans Otto Hahn, Fritz Strassman, Albert Einstein, Max Planck and all their colleagues and students. Atomic energy research was in place in the 1930s though World War II accelerated the development. The Allies sought to devise a functioning bomb because the Germans were working on getting one built, too.

If World War II is removed from the equation, the work would've certainly proceeded but probably not as deliberately, and possibly have lessened the potential for the use of atomic energy in warfare. Except, maybe, if you're a German general or political operative with severe nationalist tendencies, there's all those millions of brooding angry Russians and the pesky French and the English with all those ships. The ownership of an atomic bomb, and even a demonstration of its power in the North Sea would be enough to make anybody think twice about trying something against Germany.

Other technologies, from computers to rockets to jet propulsion to transistor radios, may have arrived slightly later than what we know, and in different places.

And, without Hitler, no autobahns for Eisenhower to see and, one may speculate, a very different urban development pattern in the U.S. if there's no real Cold War, such as we know of it. If there is a Dr. Strangelove, it's a very different kind of one, and maybe by Fritz Lang or G.W. Pabst, and in German.

And Dr. Ferdinand Porsche's opportunity to market the Volkswagen due to Hitler's desire for an inexpensive family car doesn't arise. Perhps Porsche continues his work with electric-gas hybrids, and his Beetle car of that he'd tinkered with in the early 1930s instead is designed with a mixture power train.

What about those Hemingway novels?

In terms of arts and culture, World War I is seen as the catalyst for Dada, Surrealism, the spare prose of Ernest Hemingway (who, in the the new version, has no World War I ambulance corps to join and thus, no injury to recover from), and all that delicious decadence of Weimar Germany. Writer John C. Reilly in his essay on "If Germany Won World War One" speculates on a 1918 victory, rather than the swift 1914 conclusion that is the New Worldline preference:

"Weimar culture would have happened even if there had been no Weimar Republic. We know this, since all the major themes of the Weimar period, the new art and revolutionary politics and sexual liberation, all began before the war. This was a major argument of the remarkable book, Rites of Spring by the Canadian scholar, Modris Ekstein. There would still have been Bauhaus architecture and surrealist cinema and depressing war novels if the Kaiser had issued a victory proclamation in late 1918 rather than an instrument of abdication.

Spengler with no side order of Nazis

There would even have been a Decline of The West by Oswald Spengler in 1918. He began working on it years before the war. The book was, in fact, written in part to explain the significance of a German victory. These things were simply extensions of the trends that had dominated German culture for a generation. They grew logically out of Nietzsche and Wagner and Freud. A different outcome in the First World War would probably have made the political right less suspicious of modernity, for the simple reason that left wing politics would not have been anywhere nearly as fashionable among artists as such politics were in defeat."

A 1914 victory, however, puts the German army on a tremendous high point in the nation's culture with vast influence and fulfilling the Prussian model of not a state supporting an army, but an army with a state. Marshals Hindenberg and Ludendorff are, to use a phrase, rock stars. But a draining and never-ending preoccupation with the East, and economic factors, could bubble over into civil unrest, or at least a movement toward greater participation in the political process, though what poltical stripe it would've taken is hard to say -- likely socialist. No Nazis, though.

He kept us out of a non-existent war

What of the United States? There's no reason to intervene in a European ground war that in the West is mostly finished save for the formalities of the French surrender at Versailles in the autumn of 1914. President Woodrow Wilson maintains his promise and keeps the nation out of war. The 1916 election would be interesting: Republicans nominated Charles Evan Hughes, a former New York Governor, chosen by William Howard Taft as a running mate though Hughes declined, and a U.S. Supreme Court justice, which he left to run for the presidency.

Again, from Wikipedia, the squeaker election of 1916:

"Defying election night predictions, Wilson narrowly won the election by carrying the West and South, with the outcome in doubt late into the night, when the votes came in from California, Wilson won the state by 3800 votes—and with it the presidency. Legend has it that Hughes went to bed on Election Night thinking that he was the newly elected president. When a reporter tried to telephone him to get his reaction to his loss, someone (stories vary as to whether this person was his son or a butler or valet) answered the phone and told the reporter that "the President is sleeping." The reporter retorted, "When he wakes up, tell him he isn't the President anymore."

All Gods dead...

Without German unrestricted submarine warfare as a campaign topic, that leaves criticizing Wilson's Mexican adventure and his pro-labor laws, which hurt Hughes more than it helped. I say let's give it to the judge, anyway, and shake things up.

Both of these alternative worlds are aspects for some thinking about in my fiction. And, well, yes. We are due a visit to the Blue Raccoon, where events of more current nature will also be considered.

--HEK

Labels: brane theory, contrafactual history, John Mitchell Jr., Kaiser Wilhelm II, Lewis Ginter, Maggie Walkr, Readjuster Party, Taube, William Mahone