The Only Way To Fly....

The belated return of a buoyant

alternative to getting stuck in the

middle of a four row seating arrangement

During the mid-1970s the World Book Encyclopedia featured two annual updates to its standard reference work. The Yearbooks brought you not only observations and commentaries about The Meaning of Things but an alphabetized and illustrated chronology. Then there was the Science Year and that was even more interesting. I enjoyed one volume that explored the recent discoveries at Tikal--the ancient Mayan seat--and it displayed the successive layers of the city's development with plastic overlay pages.

In 1977, however, Lee Edson contributed "Airships Make A Comeback: Lighter-than-air craft may be one solution to a number of modern transportation problems." The double page illustration that began the piece presented what resembled inflatable, prop-driven space shuttles, enormous objects, with huge passenge gondolas that looked like cruise ships. The article made the case for the airship, tracing its history from modest balloons to the astounding zeppelins and the Hindenburg crash. Times are different now, Edson wrote, and technology for airships, from construction to navigation, is far more advanced than in the 1930s. The vessels could be useful for lifting and carrying extreme cargo in remote areas or in disaster zones. Airships have an almost untlimited operating range and don't refuel very often. They can stay in one place, go low and hover, and don't use runways. (Had we freight-bearing airships for post-Katrina...)

Passenger airships received fanciful treatment in this World Book Science Year overview. The mid-1970s, bluish tint illustrations show slender people lounging and luxuriating amid Star Trek deco décor on a nuclear-powered liner.

The text made airship travel sound even more tantalizing. "One rigid-airship design based on modern technology has been drawn up by Francis Morse, professor of aerospace engineering at Boston University. His cigar-shaped craft would be about as long as the Empire State Buildng is tall Its hull would hold 354,000 cubic meters (12.5 million cubic feet) of helium in 17 gas compartments. Its most efficient operating speed would be 160 mph...

In the passenger version of this craft, Morse envisions three decks of staterooms with private bath [sic.] along the sides of the airship, a cocktail lounge and a 15-story elevator to a grand ballroom at the at the top of the airship with a huge window facing the stars. Passengers would be ferried to the airship by airplane. The plane would slow down to match the speed of the airship and then a skyhook under the airship would catch the plane and haul it inside."

But the primary reason these things weren't getting launched into the wild blue yonder: money. Somebody needed to go first. William L. Kitterman of the U.S. Energy Research and Development Administration summed it up: "You can't really make a hard-and-fast economic survey of airships, because, there are no airships to compaire with other modern transportation forms." Edson wrote, "A great deal of inertia and skepticism must be overcome if these giant craft are to return to the sky."

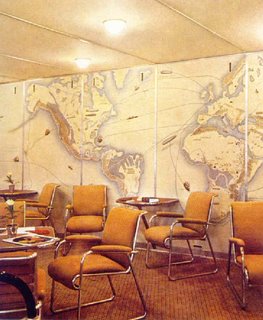

The elegant reading room aboard the Hindenburg. Today it

The elegant reading room aboard the Hindenburg. Today itcould be a wrap around plasma screen tracing the ship's progress on an animated map.

Since that World Book Encyclopedia Science Year 1977 I've held a fascination about the revival of airship transportation. And its always been on the verge. I saved articles when I could find them: The New Yorker, September 3, 1984, in a short piece titled "Blimp" about riding on the Skyship 503 piloted by Peter Buckley her "genial, trim pilot." This contains one of my favorite descriptions of what it's like to ride in an airship:

"Heading east, toward Cheseapeake Bay, the blimp passed low over stands of pine, tobacco fields, and a race track surrounded by paddocks. A man in a convertible with the top down pulled in next to the stables and took out a saddle from his back seat. Up in the air, with no wings to the sides and no blades flashing overhead, we were disconcerted, and then pleased, to realize that the sensation of staying aloft in a blimp was one that we couldn't compare to anything. When the blimp's shadow crossed the path of a horse, it whinnied, and we were close enough to see its teeth."

Round about this time in Richmond, Va., where I was still in college, I have the vivid recollection of awakening with a start from a woozy sleep on a friend's couch and hearing what sounded like airplane prop motors immediately overhead. I staggered into the alley to watch the black underside of a cigar-shaped hull drifting above, slanted across the narrow slice of sky between the houses. On the sidewalk I was treated to the emergence of the Goodyear blimp, growling its way across Richmond.

McLean's July 20, 1987, "Relaunching The Airship;" in which Vas Rotgans, president of Mandrell Mining Ltd. in Vancouver, says of airship development for heavy lifting and massive cargo transport, " We want something that is not a pipe dream but an economic tool with a specific function. A lot of people dream of floating in the air, which is nice, but it doesn't pay."

Life Magazine from sometime in the late 1980s, "Blimps: Invented nearly a century ago, they have mystery and majesty--and maybe even a future;" Popular Mechanics, July 1994 cover story, "Zeppelin's New Age of Air Travel," about the Zepplin firm's renewed interest in the vessels that made their name; Smithsonian, July 1998, "Blimps: Big, Beautiful & Everywhere You Look."

Various aerospace engineers tinkered with the formula and massaged with the shape like a birthday party clown making balloon animals: the "deltoid pumpkin seed" made famous in the wonderful John McPhee book, round ships and ships that combined the worst of dirigibles and helicopters and failing with crashes and lately, theoretical airships trying to be jets. Yet, in Europe, small tourist vessels--carrying about 20 people around in a gondola that looked like a private Lear jet--began to make runs around Lake Geneva and in Britain and elswhere.

Despite the infamous Hindenburg crash and others much less fiery and obscure--most all of them preventable--Akron, Roma, Shenandoah, Macon, and Norge-- the passenger zeps of the 1920s and 1930s cruised around the world without major mishap. If the Hindenburg had had helium gas, not hydrogen, and if the doping compound used to seal the ship's skin hadn't contained chemical compounds related to rocket fuel, static electricity might not have blown her up.

"There was little vibration, noise, rolling or pitching," wrote Kurt R. Stehling in the April 1977 Smithsonian, "There is not recorded case of air sickness on these airships. Young Nelson Rockefeller, a passenger on the Hindenburg's 1936 'Millionaire's Flight,' was supposed to have asked one of the stewards, 'When are we leaving?'

'Why, we left almost an hour ago, Sir.'

Passengers had no sense of motion and could even open promenade windows to look out, or down, from the often low altitude--around 1,000 feet--to see sights or hear events on the ground."

During the late 1980s and early 1990s I conjured my own fantastical craft and called it the Continental. It was based somewhat upon Dr. Morse's nuclear powered behemoth, but minus the nukes, instead in part running on solar power that helped operate electric motors made by BMW that could be turned round and used as fans to make the ship capable of vertical take off. Not being an engineer, I didn't solve the problem of the roustabout crew that is needed to bring down an airship and hold it in place once on the ground, nor how the immense cost of buildng hangars big enough to dock such a thing.

Continental is the realization of wealthy John "Jack" Carter, whose Commonwealth Airships Ltd. first built Pocahontas and John Rolfe for Virginia tourism, reinventing several-night passenger travel as they flitted about the state, for the Colonial and Revolutionary tours, the Civil War sites, the fall foliage Blue Ridge vista cruise, carrying and accommodating about 100 people for Friday to Sunday cruises. The success of these flights gave Carter and his team the internatioanl attention and provided investors for his firm to build Continental, an exotic hotel aloft, staffed with an international crew. The design is retro deco, sleek and sharp, with the appointments of ocean-borne cruise liner, including dancing and comedy venues, a movie theater, a pool, various restaurants, and luxe promenade suites each designed with a particular region or period of time in mind. (I'll later add my slightly updated news story about the Queen Mary 2 and Continental meeting md-Atlantic).

As I paired up with a globe-trotting artist, and began traveling more, and experiencing first-hand the drastic decline in service and amenities in commercial air travail, I yearn for an alternate. And, I also discovered the Internet.

What I found will be Part II.

The Worldwide Aeros Corporation is building this flying hotel. My dreamt of "Continental' is beginning to look possible. We're supposed to find out by 2010. At least advances in computer illustration allows for more realistic simulations.

The Worldwide Aeros Corporation is building this flying hotel. My dreamt of "Continental' is beginning to look possible. We're supposed to find out by 2010. At least advances in computer illustration allows for more realistic simulations.